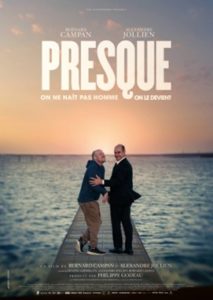

Film Review

Two almost “normal” men on a journey or the film Presque

Soledad Pereyra

Travel repeats itself as a narrative device and a metaphor for personal transformation in literature and film. To address disability, the film Presque resorts to this formula with moments of sincerity and many predictable ones.

In the realm of literature, the voyage has had great relevance since, through it, in one way or another, the very conflicts of human existence are represented. The journey in Western literature usually symbolizes an adventure and a quest, which may involve anything from factual knowledge to significant spiritual development. The premise is simple: the journey’s movement corresponds to the movement and transformation of our inner self. Particularly a genre such as the German development novel or Entwicklungsroman has often resorted to the topic of the journey to represent the mental and emotional development of the main character while he struggles with himself and his environment.

Cinema has not been far from this and, through numerous productions, has built the Road Movie genre, which seems to be an ideal narrative framework to make a story of disability and inclusion. Recently, we have already seen the use of the narrative plot of the journey to create stories linked to cognitive disability in the American Peanut Butter Falcon (2019, dir. Tyler Nilson, Michael Schwartz), in the German Die Goldfische (2019, dir. Alireza Golafshan) and the Belgian series Tytgat Chocolat (2017). This is also the case for the recently released Presque / Beautiful minds [Eng.] (2022, dir. Alexandre Jollien, Bernard Campan). Without a doubt, this choice of the cinematic subgenre and its narrative mode has a pedagogical intention concerning disability.

Almost equals

Presque is the story of two very different men who, by chance, meet and share a transformative experience. If we consider that one of these characters is a person with a disability, we can anticipate the film’s message: sharing experiences with people with disabilities can be life-changing and beneficial; it is a two-way street. On the one hand, we have Louis, a confirmed bachelor who lives dedicated to his job as a funeral director, which is the family business. On the other, we have Igor (Alexandre Jollien), a man with a disability resulting from cerebral palsy who works as a deliveryman of organic vegetables and is a dilettante philosopher who spends his free time reading Spinoza, Heidegger, and Kant.

The contrast of these two characters under the idea that they both share an outsider condition (Louis as a mortician and Igor as a person with a visible disability) represents one of the first risks of the film. With such an equation, it returns to the idea that, in the end, we are all the same. But society is not built, unfortunately, under that equality. So can the sense of otherness, alienation, and discrimination these two men suffer be placed on the same level? The film takes this risk and hints at it in the dialogue when the characters first meet and even in the many philosophical reflections of Igor.

On the road

One busy day, between one work appointment and another, Louis runs over Igor, who comes with his bicycle down the street. Louis takes him to the hospital; fortunately, he has no severe and permanent injuries. Still, the mark of the encounter will be lasting: Igor will stick with his fascination with Louis to become his comrade. Moreover, he is attracted by Louis’ profession and his work with death, so he does not leave him alone: he visits him unexpectedly at work, follows him, asks him questions, and even hides in his car and therefore remains there as a hidden passenger of the undertaker. Together they embark on a journey in Louis’ hearse from Switzerland to France to transport the body of the deceased Madeleine to the place where she is to be buried.

On this journey, Louis and Igor will conquer freedom from the gaze of others and learn to love life as it comes, freeing themselves from the prejudices that drag them down. Louis will face his loneliness, the prejudices and traumas that bind him, and his cynicism towards the world. Igor will travel for the first time away from his mother, his primary caregiver, to have a sexual encounter and live adventures away from his routine in Lausanne. Physical movement and meeting new people allow Igor to live outside of a life built around disability. This is summarized in an encounter with a woman during a night out: « Oh moi, je trouve que t’as l’air. Normal, ça ne se voit pas. » To which Igor responds without a hint of irony: « Presque. »

Dealing with taboos

The focus on the journey and on this pair of characters (who are not only personally different but also socially different because one is perceived as disabled and the other does not) allows the film to highlight, discuss and silence stereotypes about disability. For example, in the multiple scenes in which Igor talks about philosophy, the people around him seem surprised. These sequences seek to discuss the prejudice that a person with some cognitive disability (which in Igor’s case mainly affects how he verbalizes his thoughts) is incapacitated for other mental activities such as abstract thinking. In another scene, they are stopped by the police and delayed when Igor maximizes his somewhat deficient speech patterns and mimics a profound cognitive disability as this would be understood by ableism or the non-disabled. In other words, he plays dumb. Using hyperbole, Igor’s performance to get rid of the cops highlights the stereotype of disability that presumes that cognitive disability is unfailingly equivalent to idiocy and a total lack of communicative competence.

One of the film’s great successes is the sex scene between Igor and the prostitute that Louis had requested for himself and paid. It is rare to find in mass fiction films a scene where a person with a disability has sex with a person without a disability, an issue that is often hinted at and omitted (as, for example, in the acclaimed 2009 Spanish film Yo también). This scene, on the one hand, appeals to the stereotype of the asexual life of people with disabilities (Igor is shown to be inexperienced and it is implied that he is a virgin), while at the same time breaking with that idea: Igor is a grown man and has sexual desires. On the other hand, the film silences and does not further discuss the issue of professional sexual services and people with disabilities. This issue has been critically addressed in documentary films such as Yes, we fuck (2015) or the recent Spanish play, Supernormales (2022, dir. Iñaki Rikarte). However, in the movie, this situation occurs as a mere happy coincidence, even as a choice of the prostitute.

As we anticipated, this road movie is a feel-good movie with a didactic intention; it teaches us about the beautiful adventure of inclusion, where we don’t have to be defensive and scared of the disabled person, as Louis is towards Igor in the beginning of the movie. Or, as Igor would put it : « On est tous embarqués comme dans un tas. On ne sait pas ou on va. On ignore tout de la destination, mais on est à beau. » Traveling to France was not only a journey to independence and adventure to Igor, but also a journey to Louis, who stripes his heart and more (spoiler alert), opens up in the end, and sees himself as equal to Igor. When someone with a paternalistic view of the disabled Igor asks Louis: «C’est votre frère? », he now answers proudly, « Non, c’est mon ami. »